MLF Chapter & Verse

MLF Chapter & Verse

The Manchester Literature Festival Blog

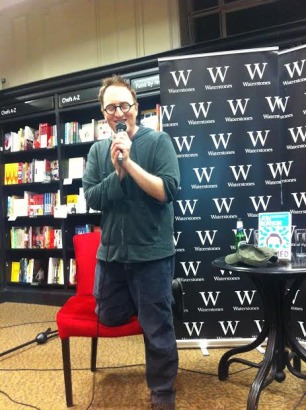

Review: Jon Ronson

Festival blogger Kate Ashley enjoys an evening with Jon Ronson and John Robb that covers everything from Twitter witch hunts to the writer’s early career in Manchester.

Jon Ronson never wanted to be a writer when he was growing up; a life spent sitting alone in a room seemed depressing and dull. But now that this is his career he has come to find spending time with other people “horrifying”. It’s a funny start to a very interesting conversation at Waterstones Deansgate, as we got behind Ronson’s need to solve mysteries Manchester Literature Festival event. That’s what Ronson does; in books ranging from the infamous Psychopath Test to the hysterical The Men Who Stare At Goats. The urge to find answers has driven Ronson throughout his writing; a motivation he says stems from a “boring childhood in surburban Cardiff”.

His latest book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, is in his own words, “terrifying”. By turning the lens around on those we shame via social media, Ronson underlines the similarities between the two groups. These people, he argues, are just like us. It is human to make mistakes, to say stupid things and to make bad jokes. Even if it wasn’t, are threats an appropriate response to offhand comments? But the ubiquity of Twitter has facilitated a Stasi-like surveillance culture; one we have created ourselves. When discussing the origins of the book, Ronson shared his own delirious joy when his followers began to harass the academic who had created a spam account using his identity.

Why do we feel such pleasure instigating the total destruction of practical strangers? It’s undoubtedly been enabled by the spread of social media, and a population which is always online. Ronson suggests that the wave of shaming started once the public realised the power it had to tear down people misusing these positions of privilege. And as these takedowns became more common, the internet started to get vicious. When there wasn’t someone to shame, we began to look for someone, anyone new. It didn’t particularly matter that things were said out of context, or misquoted; Twitter simply doesn’t allow the time for a reasoned look at the facts when the horde is baying for justice.

In this way, Ronson argues that we have, each of us on social media, become a new type of righteous troll, lightning quick to react, and with no true appreciation of the consequences a public shaming has. It’s no longer true that “the internet isn’t the real world”; if a person is destroyed online, they have to bear the scars in their nonvirtual life too. The book weaves these questions around the case studies of real people who have been shamed. It’s the first time many will stop to think about the way we use crowd mentality, the way we escalate our vitriol, and the deep, dark fear that it could one day be the other way around. Any of us could be the victim.

__

Kate Ashley is a Manchester-based writer who blogs at Kookooburra.