MLF Chapter & Verse

MLF Chapter & Verse

The Manchester Literature Festival Blog

Review: Lyndall Gordon

MLF young digital reporter Jess Molyneux reviews our event with Outsiders author Lyndall Gordon

Assembled under the Portico Library’s famous blue domed ceiling, it really did feel that we were seated at the heart of a Manchester which has been a thriving centre of culture and intellect for centuries. At once quaint and magnificent, this hidden gem of a central location was perfect for Lyndall Gordon’s quietly ground-breaking discussion with Libby Tempest, chair of the Elizabeth Gaskell society. Add an event at the Portico to your list of must-dos at next year’s festival.

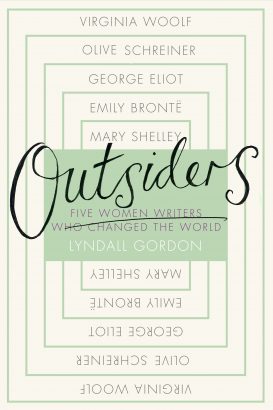

Lyndall was introduced as a ‘biographer with soul’ who explores and amplifies the ‘inner life and creativity of her subjects’. She certainly had a lot of material to work with in her new book Outsiders: Five Women Writers Who Changed the World, which looks at Mary Shelley, Emily Brontë, George Eliot, Olive Schreiner, and Virginia Woolf, and we sensed in the comparatively brief snapshot which the evening gave us of Lyndall’s biographical prowess that this was well-deserved praise. Her encyclopaedic knowledge of her subjects was frequently, though subtly, showcased as she recounted innumerable intimate and revealing anecdotes and quotations from novels and letters with impressive fluency.

Before a discussion with Libby and the audience, Lyndall outlined just how much these five extraordinary authoresses had in common: most notably, all thought of themselves as outsiders, ‘freaks of nature’ as George Eliot put it, and Lyndall sought to bring them together, to track this ‘rising phenomena’ of women who were somehow and in various ways at odds with society, this ‘rare breed’ who shared a genius.

Other superficial similarities abounded, and through Lyndall’s talk we began to see the strength of the extraordinary thread which united these women. All were motherless, or effectively so, helped by ‘an enlightened man’ (think Percy Shelley, George Henry Lewes, Leonard Woolf, Patrick Bronte), and readers before writers (and readers of one another). Mary Wollstonecraft (Mary Shelley’s mother and author of the proto-feminist A Vindication of Women’s Rights) continually recurred as the ‘common ancestor’, as it were, whose revolutionary ideas are echoed in some way or another by all five.

Libby’s unimposingly thorough questioning opened up the exploration of these amazing women writers. The absent figures who we might have expected to see in a book about great women writers (think Emily Dickinson) were discussed; limits of time and space were regretted. Libby worked through the authors steadily, prompting Lyndall to expand on each in their turn. Links between these great women continued to emerge, as the varying degrees of their outsider status were discussed and we learnt more about Olive Schreiner, the least familiar of these greats.

Audience questions touched on the difference between male and female biographers (Lyndall concluded that more experimental works tend to come from women), and another notably absent figure: Jane Austen.