MLF Chapter & Verse

MLF Chapter & Verse

The Manchester Literature Festival Blog

Review: ‘I was called to this work.’ Patrisse Khan-Cullors

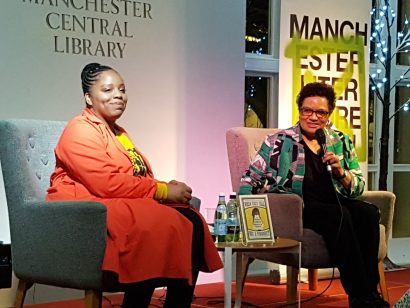

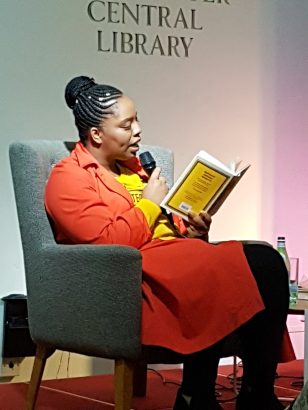

Manchester Central Library is packed on a cold, March evening with one of the most varied audiences I’ve been part of at a literary event. We’re here to listen to Patrisse Khan-Cullors, co-founder of Black Lives Matter and co-author of the book When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir. She’s interviewed by Festival patron, writer and Scottish Makar, Jackie Kay.

Kay begins by introducing Khan-Cullors in a long line of black, feminist, activist writers including Angela Davis, who wrote the forward to the book. In response, Khan-Cullors says she thinks about her ancestors all the time. They motivate her for the work she does, which she describes as often thankless and tiring.

They begin by discussing Khan-Cullors’ childhood. Kay describes the section in the book where Khan-Cullors’ house was raided by police. She was nine. Kay describes what’s considered to be the universal childhood experience, one of freedom and innocence, pointing out that this is an association with white childhood.

‘We didn’t talk about what we were going through, we just lived it,’ says Khan-Cullors. She says that writing about the consistent trauma of her childhood meant confronting it for the first time. Her feelings towards her younger self changed, she felt more compassion towards who she was. It also helped her to understand what her mother was going through at the time.

Kay asks about the way the book is structured. Khan-Cullors says it’s structured around her life – the war on drugs and the war on gangs. She was interested in exploring the impact of policing on black women as they are the ones at home dealing with the brunt of it. ‘It’s the things that hurt us the most that bring us into activism. It’s a matter of life and death.’

The discussion continues around the way policing affects the community. Kay and Khan-Cullors discuss the idea of moving away from the area you grew up in if you can afford to in adulthood. Khan-Cullors says that she doesn’t understand this way of thinking, she wants to remain part of her community and bring it with her, not leave it behind.

Kay moves on to talking about Khan-Cullors’ family, specifically her biological father and her brother. Khan-Cullors didn’t meet her biological father until she was 11. She recalls thinking that the meeting would be like a television show reunion but instead it was strange and awkward. However, her relationship with her biological father became a model for the type of life she wanted to live. ‘It was the first time in my life an adult was honest about his flaws.’ Kay mentions how the Khan-Cullors’ family move apart and come back together after absences, saying that the role her father plays in bringing people together reminds her of the way in which Khan-Cullors brings people together. Khan-Cullors is delighted, acknowledging that it’s the first time someone has made that link.

They talk about her brother, Monte. ‘We lived in a place, in a country, in a world that rejected him for being black, scary, mentally ill, a convicted felon. I had to figure out how to be there for him.’ He was in the criminal justice system by the time he was 18 but Khan-Cullors thinks that could’ve been avoided if there was better care for people with mental health illnesses and if black lives weren’t criminalised. She says that mental health care is an issue in the UK as well as the USA.

‘I had a lot of rage and a lot of sadness,’ she says of her younger self. She mentions the writers and activists she saw as mentors who gave her hope, including Audre Lorde, bell hooks and Emma Goldman. They gave her a language around racism, feminism and sexism. ‘Some of us were called to this work. I was called to this work.’

Kay mentions room in the movement for black lesbians – Khan-Cullors identifies as queer – and they discuss how Audre Lorde and her work helped to carve this space. ‘So many of us look to the Lorde for affirmation,’ says Khan-Cullors.

Kay emphasises that Black Lives Matter was founded by three women: Khan-Cullors,

Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi. Khan-Cullors says that one day she won’t have to tell people that, they’ll know! She talks about how the movement began following the verdict in the trial of George Zimmerman. Trayvon Martin’s family were humiliated during the trial, it was as though their son was having to prove his innocence. Khan-Cullors felt betrayed by the verdict and went on social media to see what others were saying about it. Alicia Garza had written a love letter to black people with the phrase Black Lives Matter included. Khan-Cullors suggested they added a hashtag to it. Later, Opal Tometi, who has experience organising protests, joined them. Khan-Cullors describes the murder of Michael Brown as ‘the moment when Black Lives Matter went global’. They’d spent a year building the movement and then they mobilised as a team; 600 people from 18 states went to Ferguson to protest.

Before the discussion is opened to questions from the audience, Kay asks Khan-Cullors about the election of Donald Trump to The White House. ‘November 8th was a tragedy for me. I was scared for my own personal safety.’ She says there are decisions to be made about where the movement goes next.

Which leads nicely on to the first audience question, which is about resilience and engagement of young people and what they can do to support the movement. The question is addressed to both Kay and Khan-Cullors. Kay responds by saying they should get involved, use their voice, never be afraid of being who they are and join with like-minded people. She points to Khan-Cullors, who’s 34, as a great role model. Khan-Cullors says, ‘It’s our job and duty as human beings to make this planet better for the next generation. Wherever you are, you change where you are. The local is so important. We’ve got to look at the terrible things happening here [in the UK].’ Do we know the names of people who’ve died in custody? Do we know who’s living in poverty?

The next question is about how you choose your battles. ‘My 16-year-old self was fire. I dealt with everything. At some moments you have to say something but you do have to choose your battles for your sanity and your health. It’s about your purpose; I’m a campaigner.’ Khan-Cullors says that she was asked by a journalist whether she’d meet with 45 [Donald Trump]. She responded by asking what the purpose of that meeting would be. Her agenda is to get him out of office in 2020.

Khan-Cullors is asked how the Black Lives Matter campaign got people’s attention and outrage and how that can be replicated in the UK. She says she can’t speak about other countries where the situation is different but that it took decades for people in the US to be outraged and that once the cameras were on them, they turned away again just as quickly. ‘Wherever we are, racism exists. Wherever we are, we do the work.’

Someone else asks whether Khan-Cullors thinks her sexuality has stopped some people from supporting the movement. ‘We are a generation that fights for all black lives. We have to. This isn’t about a philosophy, this is about survival.’ She talks about discovering the black women and men who were queer writers, artists and activists. ‘No one mentioned they were queer. It was such an affirmation to me.’

Kay asks about the impact of Black Lives Matter. Khan-Cullors says it’s been bigger ‘than I ever imagined – myself, my trajectory, but also the world. It’s a survivor’s story.’

Jackie Kay ends by thanking Patrisse Khan-Cullors for being ‘an absolute inspiration’. It’s pretty clear that the audience agree with Kay’s words as they give Khan-Cullors a standing ovation.