MLF Chapter & Verse

MLF Chapter & Verse

The Manchester Literature Festival Blog

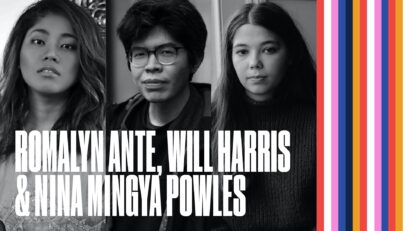

Review: Romalyn Ante, Will Harris & Nina Mingya Powles

Young Digital Reporter Jamie King finds words that echo through the generations at Romalyn Ante, Will Harris & Nina Mingya Powles.

As the rainclouds open over Manchester, legions of poetry lovers huddle over their computers waiting to hear the words of three people who pierce the veil of everyday drudgery, finding incredible stories behind it.

‘It’s really nice this is live,’ says Will Harris. ‘It has a kind of live frisson. Like, I could spill water on my laptop at any point’.

In bringing these three poets together for an hour, Manchester Literature Festival has created a brief snapshot of the vital and vibrant contributions poets of East Asian heritage are making to UK culture right now. The large, enthusiastic audience demonstrates how eager readers are to hear and soak up their words.

Our host, Becky Swain, begins by romanticising the internet connection, calling it a ‘virtual poetry lay line’. The natural imagery seems fitting as we begin with award-winning nature writer Nina Mingya Powles.

In her visceral ‘Last Eclipse’, a character – simply ‘she’ – is overwhelmed and destroyed by nature, but the words are smooth, and her delivery is tender. ‘She dissolved with blue light into orchards / She became a colour never seen’. As her body is destroyed by the natural landscape, she finds peace and abandon.

It is colours which often ignite Nina’s poetry, and Becky describes the ‘museum of colour in Nina’s work. ‘Maybe that’s what I’m always trying to do in my poems’, Nina considers, ‘Because I’m obsessed with colours, and I always have been. I love the challenge of finding new words for new colours’.

She innovates too, by shifting between languages in her poems. ‘That was something I started doing early on, using Chinese characters in my poems, but I wasn’t sure if it was really okay to do that. But I just sort of did it anyway.’ She laughs and notes that, having a limited grasp of Chinese, she wants to ‘present language on the page as it is for me in my reality’.

The well-paced incantations in her poems inspire Will Harris, as he chooses to kick off with ‘Buddleia Not Buddha’, a rhythmic, tightly held dash through a rollocking city and rollocking emotions. ‘buddleia not buddha chanting in bloom / buddleia not buddha buddling on my tomb.’ It is, he says, ‘A kind of spell or incantation to ward away sadness, or loneliness generally’. Perhaps loneliness isn’t what a reader expects from a character passing so many people in such a big city, but here Will may have hit a nerve in the daily life of many Mancunians.

The city is a major character in another poem he selects, as the London Underground weaves delicate threads between family members in his ‘Half Got Out’. A phrase borrowed from Ben Jonson’s description of a baby mid-birth.

‘I could be seeing my / parents right now who / live ten stops away yes / half an hour but I’m / not and what else am I / not doing’. Throughout the poem, the speaker meets other London characters who are also getting further and further away from their parents and grandparents, but with that family thread still tugging inside.

Sketching vivid characters in a few powerful words is one of Will’s great strengths, as anyone who has read his superb poem ‘My Name is Dai’ can attest. And it is his relationships to these people that seem to really motivate him.

‘For me, the address is important, I started writing poems to people,’ he explains. ‘They started to mean something to me when they were less me-based.’

But the most memorable characters of the afternoon come from the poems of Romalyn Ante. Indeed, Romalyn herself is one incredible character. She writes between shifts as a full-time specialist nurse practitioner in the West Midlands NHS, and her latest book, Antiemetic for Homesickness, is rich with the images and gut-punches of a working life on the hospital ward.

Say United Kingdom, say the queen, NHS.

Does winter always mean – ?

Listen – can you hear it? The loneliness

of stretchers queued along A&E corridors.

Surely, in the days of coronavirus, a book of poems written by an NHS nurse about her experiences deserves major national recognition. I mean, they gave Joe Wicks an MBE. Romalyn Ante should at least be invited on The One Show.

Her real knockout work is ‘Group Portrait at the Stopover’, which she reads at the end of her set. Romalyn’s writing often gives powerful, delicate insights into her Filipino family, but in this poem, she summons the spectacle of a whole nation, displaced in an airport lounge, sharing food from the variety of countries they have most recently been employed in.

‘Elbow to elbow on waiting chairs’ the Filipino overseas workers exchange butter fudge and incredible stories. Romalyn says she is particularly interested in those who are ‘exiled through employment’ and the astonishing repetition of the same worker migration, generation after generation, daughter after mother.

‘Tara na, let’s not think, / for now, of the next generation that will meet at this gate, / the same old stories that will hum out of younger mouths.’

She tells us how the scene she came across – of Filipino workers at a Dubai airport – ‘filled me with such joy, but such sadness at the same time. Joy because I realised that, even after so many years, Filipinos still choose to leave, in order to rebuild, and build the life that they want for their loved ones, so there’s an honour in that. But also sadness because, after so many years, the Philippines, and I’m sure many other countries, continue to let their people down. They cannot provide economic security after all those years’.

This is the most intimate Manchester Literature Festival ever held. As Will Harris looks directly at you and reads poetry about the death of his grandmother, you can’t not feel it. Indeed, it’s interesting that all three of these young poets read something about their grandmother, or their mother. Nina Mingya Powles, Will Harris and Romalyn Ante have been grouped together at this event because of their heritage, and their hour of poetry shows us that if ‘heritage’ means anything, it means family. It means people, standing back in time, or waiting sat by the phone. Waiting for you.

The work of these East Asian diaspora writers is not simply the poems wrought from one section of the map. These are the poems of grandchildren.