MLF Chapter & Verse

MLF Chapter & Verse

The Manchester Literature Festival Blog

Review: Rebecca Solnit

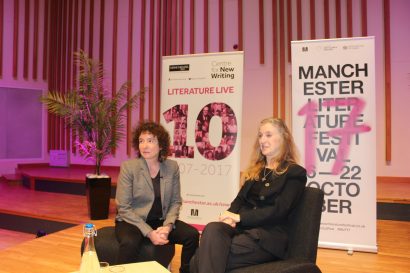

Young Digital Reporter Jess Molyneux enjoys an evening with Rebecca Solnit and Jeanette Winterson

What better note to start on, to combat any jitters we might have had on a wintry Halloween evening, than that Manchester had very recently been pronounced a UNESCO City of Literature. Glowing with pride in that home town of ours which has nurtured the likes of Elizabeth Gaskell, Anthony Burgess and Jeanette Winterson (our host for the evening), we became the spectators of the first event Manchester hosted with its brand-new accolade.

A brief introduction could only show us a glimpse of the successes which these two influential women writers have enjoyed, though the easy, shrewd, and witty conversation which followed did much to expand our insight.

Rebecca Solnit has been an activist since the 1990s, and earned recognition for her now-renowned essay Men Explain Things to Me. Her recently published book The Mother of All Questions is an essay collection of ‘further feminisms’, and continues her perceptive commentary on women’s place in the world today. She has written on a variety of other subjects, including climate change and the history of walking, and was described as ‘uniting the personal and the political’.

Jeanette Winterson’s debut coming-of-age novel-cum-autobiography, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, won the Whitbread Award for a First Novel in 1985. In 2016, she was chosen as one of BBC’s 100 Women and is currently a professor at the Centre for New Writing at the University of Manchester.

Solnit begun by reading a passage from her new book, in which she describes the single life plot offered to women, the one-size-fits-all universal formula for happiness, which led into conversation with Winterson about silencing in society, and noting its particular relevance at a time when the front pages are plastered with Weinstein headlines.

From the annoyances of mansplaining, to the lost potential of an oppressed Sylvia Plath (who, Winterson suggested, despite her genius, may still be a form of Virginia Woolf’s ‘Judith Shakespeare’), the dangerous impacts of silencing were a running theme of the discussion. Solnit points out how easily the (relatively) harmless arrogance of ‘you don’t know how to read Lolita’ can soon become ‘you don’t know how to interpret your own experience’.

Solnit does recognise, though, the ways in which events like the Weinstein scandal can be seen as ‘seismic lurches’. She compared the ‘epic breaking of silence’ which unearthed, and has been a result of, the Weinstein scandal to Anita Hill’s breakthrough in the early 1990s which changed the way we think and talk about sexual harassment, citing the show of solidarity through bumper stickers (before hashtags existed).

Refreshingly, though, Solnit’s feminism is distinctly optimistic and open-minded: she manages to remain stirringly forward-looking whilst celebrating the achievements of the past. ‘Ideas are genies’, she commented; ideas like ‘women and men might be equal’ or ‘marriage with someone of your own sex is okay’ aren’t going back in the bottle. Though Solnit described part of feminism’s current role as ‘maintenance work’, and Winterson likened it to ‘a f***ing rock’ which keeps sliding back down the mountain as we push it up, Solnit urged us to see our trajectory across time. Young women are experiencing the changes that feminism has made (often without realising it) and Solnit sees progress in the ways men are accepting that they have a role too, and boys are being raised without a misogynistic sense of entitlement.

Solnit joined her final thanks to the audience ‘for being part of the revolution’ with a parting hope that one day these types of stories will simply disappear, and an injunction to the patriarchy, a strong incentive for it to work for the feminist cause: ‘you can make my books obsolete – destroy yourself and, with that, my revenue’.

I don’t think the world is quite ready to lose its Rebecca Solnit, but hopefully one day it won’t need her quite so much as it does now.